Bram Stoker was a sickly child, he saw more of his mother than any of his other siblings. She liked to entertain him with stories drawn from her early life in Sligo and Donegal, and from her own family history of the Blakes and O’Donnells. View the Blake family tree.

Blakes

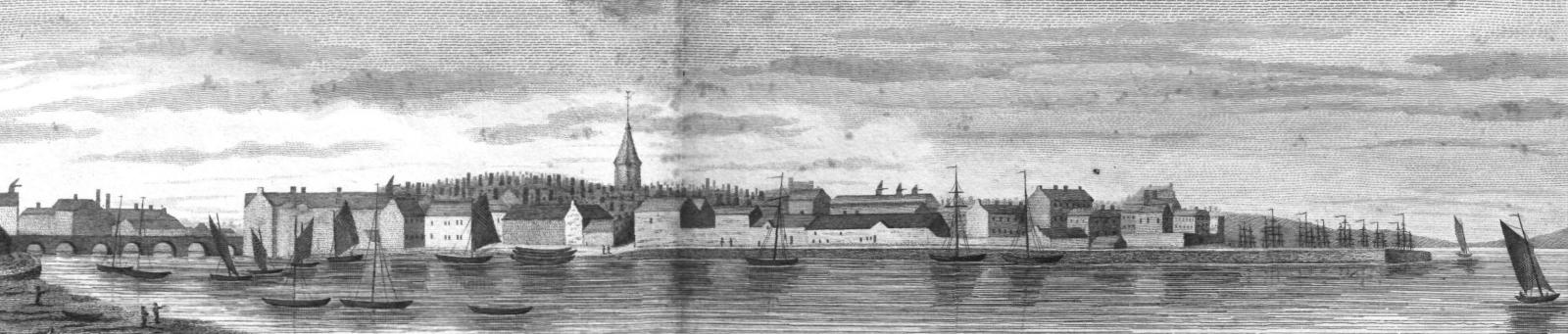

The Blake family were one of the ‘Tribes of Galway’. They settled in Connacht (the western province) by the 14th Century, and were mariners and merchant princes. They owned sea-going ships and traded goods with ports on the western coast of France, and Spain. They exported timber and leather hides, and imported wines, silks and spices.

After Hardiman’s History of Galway

Matilda Blake (Bram’s grandmother) had an interesting family. She was a younger daughter of Richard Blake and Eliza O’Donnell. Her oldest brother ‘General’ George Blake led the Irish rebels in Connacht in 1798, and fought beside General Humbert’s troops.

George Blake (Bram’s Great-Uncle)

In the 1798 Rebellion, ‘General’ George Blake led the Irish forces, estimated as 1,500 mainly pikemen and cavalry, in the Battle of Ballinamuck co. Longford, on 8th September 1798. General Humbert led the French force of 800.

The Irish rebels were hopelessly ill equipped, armed mainly with pikes which they used as bayonets, they faced an army equipped with guns and heavy artillery.

The rebels were outmanoeuvred and massively outnumbered by General Lake’s crown forces. The French surrendered without terms. General Lake then undertook a wholesale slaughter of the Irish rebels. Best estimates indicate approximately 500 to 600 were killed in battle, and hundreds hanged afterwards.

Local tradition records that there were so many Irish rebels, that the crown forces held a lottery using cards marked ‘life’ and ‘death’ to reduce the executions to more manageable numbers. Those who drew ‘life’cards were set free. Those prisoners that drew ‘death’ were taken to be hanged at Ballinalee (MacGréine, ‘Traditions of 1798′, pp 393-5; 1798 Commemoration, p.12).

George Blake was captured several days after the battle and was hanged at Kiltycreevagh Hill (The English brought the prisoner’s to Jack Griffin’s house in Coillte Craobhach, and the first man they hung was General Blake’. IFC 1858 97-8 IFC S758: 55, IFC S760: 477 Irish Folklore Commission, University College Dublin).

We found a contemporary newspaper account of Blake’s death:

Blake, the insurgent leader, who had joined the French, and was lately deservedly hanged as a traitor; begged to be shot. When that was refused, he requested to be indulged with the noose of the rope that was for his execution being soaped, that it might run free to shorten the time of dying. This, we hear, was granted, and he prepared it in that manner with his own hand.

Freeman’s Journal 15 September 1798

These stories about 1798 and about the gruesome end met by ‘General’ George Blake and the rebels were widely known across Ireland. When Bram heard them, he would have had the added frisson of knowing that George Blake was his great-uncle and that he led an estimated 800 to 1000 Irishmen to their deaths.

O’Donnells

Charlotte had other family stories about her O’Donnell ancestors, including one which provided a link between the ancient past and Bram’s early childhood.

In 1843 Sir Richard O’Donell, Charlotte Stoker’s close cousin, deposited some ancient artefacts with the Royal Irish Academy.

These artefacts – – the psalter of St. Columbcille and the shrine that held it – had been passed down by descent within the O’Donnell family, between 561 A.D. and 1843 A.D.

O’Donnell’s decision to donate them was inspired by the ‘Celtic Revival’ – a renewed interest in the lost classical history and culture of Ireland.

His donation was enthusiastically covered by the Irish newspapers, and was a cause célèbre.

What was the Psalter of St. Columbcille?

The psalter of Columbcille, also known as the ‘Cathach’ is the earliest surviving Irish manuscript. Linguistically it has been shown to date from the second half of the 6th Century or early 7th Century.

The psalter is a vulgate copy of the Psalms 30(10) to 105(13), by tradition it was copied by St. Columbcille’s own hand.

Vulgate means it was written in the everyday latin that was spoken in the Roman empire in the 3rd and 4th centuries A.D.

Who was St. Columbcille?

Columbcille was born c. 521, and died 597.

The defining act of his life was to leave Ireland, to be ‘a pilgrim of Christ in Britain’.

He founded the monastery of Iona and monasteries in Derry and Durrow.

Columbcille was revered in Ireland as the patron saint of poets.

How did the O’Donnells become hereditary keepers of St. Columbcille’s Psalter?

In 561 A.D., after the battle of Cul Dremna, Columbcille’s Psalter passed into the hands of the O’Donnells, who remained the hereditary keepers of this manuscript book until 1842.

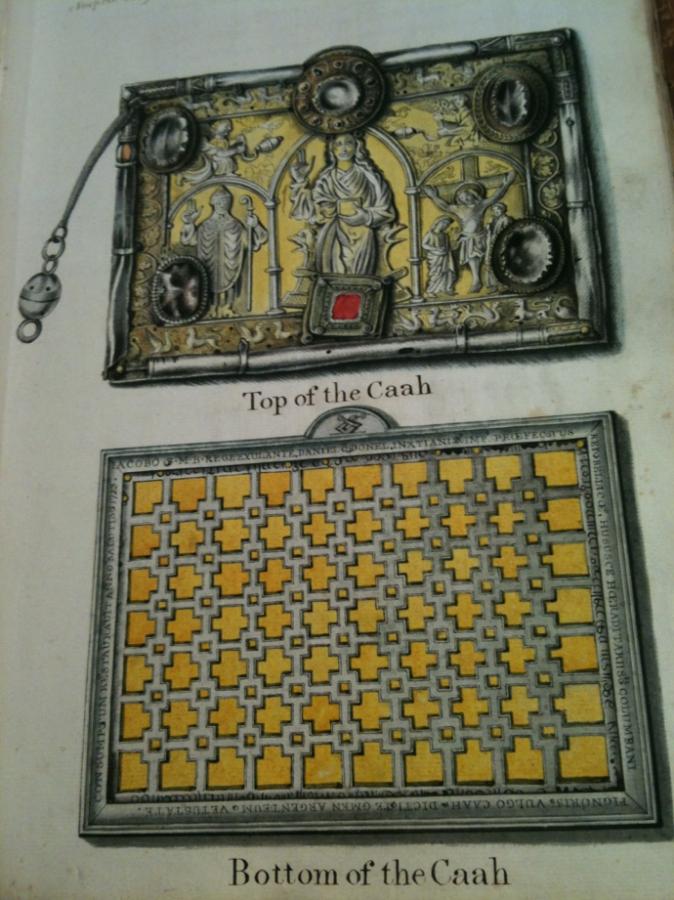

Ca. 1092 A.D., the O’Donnells commissioned a new shrine to hold the psalter. The shrone was decorated with cystals, pearls and silver tracework, with an inscription in Irish around the base.

How did the Psalter become known as the Cathach?

In the medieval period the manuscript was used by the O’Donnells for another purpose:

the manuscript was named ‘Cathach’ or ‘Battler’ from the practice of carrying it thrice right-hand-wise … as a talisman [before battle].It was taken to France in 1691 and brought back to Sir Neal O’Donel, Newport, Co. Mayo, in 1802 (Royal Irish Academy)

How did the psalter came into the possession of the O’Donnells of Newport?

In 1691 the manuscript-book and shrine were taken to France. When the last of this family died without children, the book and shrine were bequeathed to their closest O’Donnell relatives in Ireland – the O’Donnells of Newport. In 1802 the book and shrine were returned in a trunk to Ireland.In 1813 the renowned genealogist William Betham, was invited to inspect the contents of the chest. He opened the trunk, to discover the battered but elaborately decorated box, containing the book.

What was the relevance of all of this to Bram Stoker’s family?

In 1813 the ‘rediscovery’ of St. Columbcille’s psalter in a trunk bequeathed by the last of the O’Donnnells in France, had a dynastic importance. William Betham wrote “it was a tacit acknowledgement that the O’Donnells of Newport [were] now the chief of this illustrious family.”Charlotte Stoker knew that her own grandmother was born into the O’Donnell family of Newport, and that she could claim descent from this line too.

Through his maternal line, we can trace Bram Stoker’s descent in twelve generations from Manus O’Donnell (Manus ‘the Magnificent’), Lord of Tir Conaill who died in 1563. View the O’Donnell family tree.

We can trace this direct lineage back even earlier, because the O’Donnell lords from whom Bram Stoker is directly descended, were one of the oldest recorded lineages in Ireland. Bram Stoker could trace his own direct family line back not as a ‘clan member’ but as a direct descendant.

View the O’Donnells of Tir Conaill family tree

(After T.W. Moody, F.X. Martin & F.J. Byrne, 1984, A New History of Ireland: IX, Maps, genealogies, lists. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 145)

In fact, through the evidence of the ‘Cathach’ and the shrine, which were passed by descent within the O’Donnell family, we have de facto evidence of Bram Stoker’s O’Donnell direct lineage, back to 561 A.D.

Do these artefacts survive today?

The Cathach or Psalter of St. Columbcille is held by the Royal Irish Academy on Dawson Street.The reliquary was also deposited, and today is on display in the National Museum of Ireland on Kildare Street.